The Renaissance of the Classic Big-Bore Express Rifle

When Ruger announced its Magnum Express rifle in 1991, chambered in the venerable and long extinct .416 Rigby, it was a signal moment. It marked the renaissance of the big bore rifle and of African safaris. For two decades, big bore had meant anything over .30 caliber and interest in such cartridges fell precipitously when discussing anything larger than the .338 Winchester Magnum. The .375 Holland & Holland Magnum was considered overpowered for even the largest game in North America. Winchester's big .458, itself a stop gap against the sudden collapse of the British gun trade in the 1950s, saw less and less use as the 1970s came to a close. In practical terms, big bore for Americans meant the .45-70 Government. Anything more potent was gross and absurd. "What are you gonna do with that thing? Hunt elephants?" Hunting the Big Five of Africa was a subject that drew practically no following and the rare special issues of shooting periodicals to cover such subjects were coveted by a dwindling few.

The affluence of the late 1980s changed that. Suddenly, Americans had the resources to take extravagant holidays and a select number began to contemplate hunting Africa. Whether Ruger precipitated this resurgence or merely recognized it I will leave to others to judge, but undeniably Ruger made the strongest statement with its decision to reintroduce one of the classic British big game cartridges in its new magnum length express action. The rifle also bore numerous marks of being consciously cast in the mold of classic vintage Mauser sporting rifles by British gunmakers (they advertised it as "Bond Street" quality), with its square receiver bridge, quarter rib, barrel banded swivel and express sights. The newly redesigned Mk II action itself, introduced in 1989, hearkened back to the classic English-built Mauser with its lines and especially its strong claw extractor running the length of the bolt as on the Mauser Model 1898. When it appeared in the 1992 production year, Ruger's Magnum Express was the only commercially available bolt action that could handle the big .416 Rigby without extensive modification (recall that the Cold War was still ongoing, in the US if nowhere else, and the CZ ZKK 602 was banned from importation into the US, though a few managed to get in, because they were brought in by military personnel who bought them in Germany). Interestingly, although they purportedly only manufactured 1000, Ruger built far more .416s than did John Rigby & Co. during its heyday (only 189 pre-war magnum Mausers were built), which is a significant statement on the popularity of the hunting of African big game with big bore magazine express rifles, past and present.

The Ruger RSM Model 77 Mk II Magnum Express rifle in .416 Rigby

The Ruger Hawkeye African, the last surviving vestige of the magnificent Ruger Model 77 Mk II rifles

Yes, the .416 Remington Magnum had been introduced three years previously and it's a magnificent cartridge - more practical by far than the big Rigby. It is arguably the best dangerous game big bore cartridge developed since the classic .404 Jeffery. However the Remington Model 700 rifle bears no resemblance to the vintage classics of the golden era of African hunting and its extractor is so unreliable that anyone using it for dangerous game hunting is literally taking his life in his hands in a way that perhaps he little reckons (I know, I know... I never had a problem with Remington extractors either - until I did...). The .416 Remington Magnum is now (and has been for years) offered by the Winchester Custom Shop in its Model 70 Safari Express rifles, but that came later. Unlike the modern push-feed Remington action, the Magnum Ruger responded to the reawakened desire for the vintage original British big bore rifle with classic style in a classic chambering.

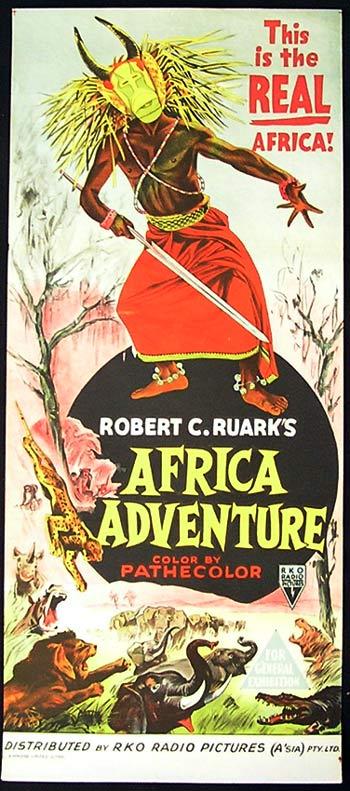

And the .416 Rigby is classic. Legendary even, perhaps as much for its eventual scarcity as for its reputed effectiveness. I won't bother to repeat the oft quoted line by John "Pondoro" Taylor about its efficacy on lions, but he gave it high praise for all big game, which is saying something since he was not a big fan of magazine rifles generally. A lot of that had to do with Rigby's steel jacketed solids. Harry Selby is the most famous user of the .416 Rigby, first achieving recognition at a very young age in the 1950s as a result of the literary and film exploits of writer Robert Ruark (try to get a pristine copy of RKO's Africa Adventure from 1954 to see young Harry Selby in the waning years of the golden age of safari when Africa was still a wild place and things were not yet commercialized). He used his Rigby rifle, nicknamed "Skitini" by his trackers, for 40 years as a professional hunter, beginning in 1949 when his .470 Nitro Express double was destroyed by a mishap. Amazingly, his Rigby rifle was not one of the big magnum length Mausers, rather it was custom built on a highly modified standard military Mauser 98 action; something that conventional wisdom holds to be impossible. My brother and I have pondered over the judicious removal of steel in the receiver to make that work. Because few gunsmiths were skilled and daring enough to attempt such surgery, the big .416 Rigby was generally limited to magnum Mausers, which were never in abundance and quite expensive. I think this is surely one reason why the .404 Jeffery assumed greater prominence; its not a better cartridge, but it can more easily be adapted to a standard 98 Mauser and has continued to be loaded and chambered by the Europeans since its introduction.

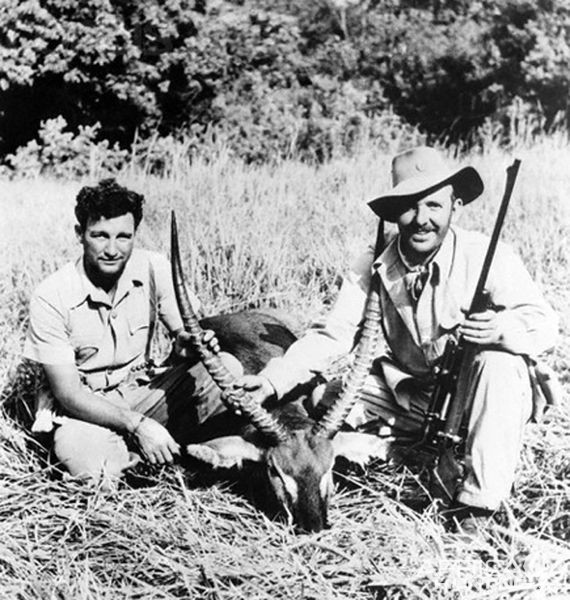

Harry Selby and Robert Ruark on safari in Kenya in the 1950s, and the poster from the film

Re-Making the Ruger in Retro-Vintage Style

Style & Substance

Unfortunately, the (sadly discontinued) Ruger RSM Model 77 Mk II Magnum Express had three serious flaws:

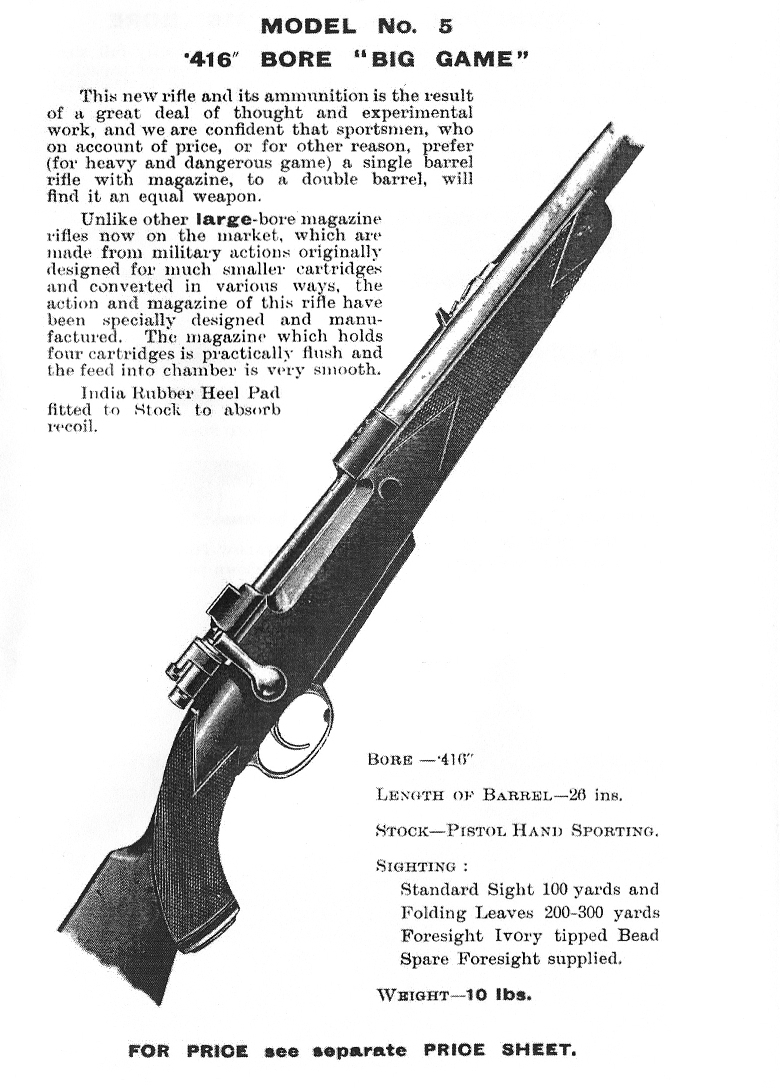

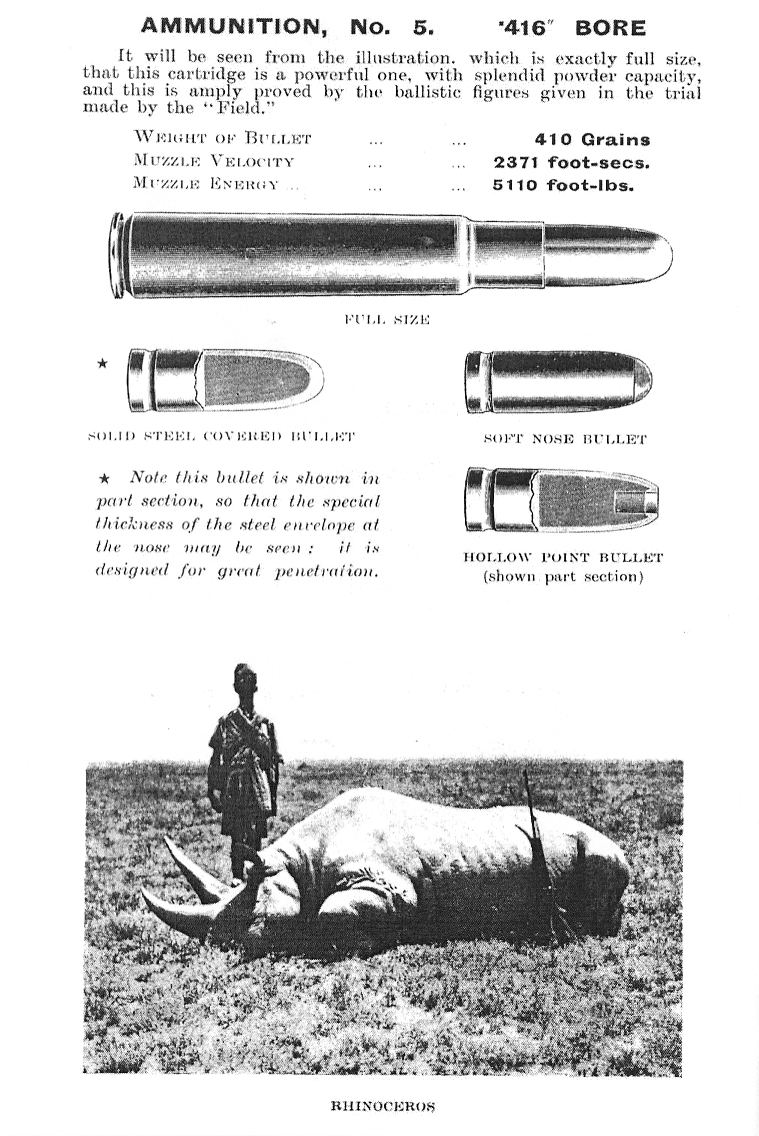

Below are two pages of an early John Rigby & Co. catalog depicting the new .416 Rigby cartridge in the big magnum length Mauser sporting rifle. Note the long straight bolt handle and simple classic styling. Note also the weight of the rifle (10 lbs) and the barrel length of 26 inches. Short of rebarreling the Ruger there is nothing to be done about the barrel length (the Ruger has a 23 inch barrel) and I wouldn't want to anyway because one of the foremost points of appeal on that Ruger Model 77 Mk II Magnum rifle is the one-piece forged barrel with its integral quarter rib. However, a new bolt handle and stock would transform this rifle into something at once more functional and more aesthetically pleasing.

John Rigby catalog advertisement for a Mauser sporting rifle in .416 Rigby caliber

Bolt Handle Replacement

Drawing on the above list of design faults in the factory Ruger, there is first the bolt handle to be rectified. It is too sculpted to be reshaped and that is not a very satisfactory approach anyway. The only answer is to cut it off and weld on a replacement. I contracted that work with Stuart Satterlee of Satterlee Arms after I discovered his website and perused his replacement bolts for Mausers done in the classic traditional sporting style. I asked Stuart for a massive and muscular bolt handle, long and straight with a teardrop-shaped bolt knob. Nothing slender or dainty here. This rifle is robust and the bolt handle needs to match. After market ready made replacements tend to be too gracile for this application. Stuart had to make something especially for this purpose but the result is fantastic and the price was quite reasonable. I intend to seek his talents again in future on a Mauser sporting rifle project.

Custom Gunstock

I searched long and hard for a stockmaker who would make a traditional styled stock pattern with a pancake cheekpiece, a long open wrist and a little drop at the heel (notice that I don't use the word "classic" here - that denotes something else entirely). The difficulty was finding anyone who had a pattern for the Ruger M77 MkII Magnum. I had a pattern stock made by Great American Gunstocks, but evidently Ruger modified their recoil lug and stock bolt at some point because the inletting was different and so that was not usable (it also was not what I asked for - it had a pancake cheekpiece but was otherwise identical to the factory stock).

Then I saw that Paul and Sharon Dressel began to advertise stockmaking and pattern copying, so I inquired. I was contacted by a fellow named Sandy McDonald, who is their resident gunsmith and stockmaker. We discussed the problem and on Sandy's advice I decided to let him inlet the action in a blank by hand and then carve a pattern, rather than use the factory stock to facilitate making a pattern (it was just too different). This was, he felt, the only means of ensuring that the action would be properly inletted with a stock pattern. Its doing it the hard way, but there really was no other way.

This pattern was fully inletted and glass bedded. It had a recoil pad and grip cap. The idea was to make the pattern perfect so that when it was duplicated the final fitting of the actual gunstock would be minimal. After he made the pattern, he shipped it to me for my review. My brother was going to do the final fitting, shaping and finishing for me and so I had him look it over. Then I shipped it back to Dressel's for Sandy to duplicate the pattern with my California English walnut blank. Below is the blank that I selected for this gunstock. It has relatively straight grain flow through the wrist and action area for strength, but nice mineral streaking.

The beginning: a California English walnut stock blank from Paul & Sharon Dressel

Recoil Lug

Sandy is a very capable and meticulous gunsmith. Before the stock pattern was begun, he set about rebuilding the recoil lug. We discussed this at length and he agreed that the factory design was needlessly complicated. His suggestion was to machine a dovetail into the massive rib underneath the barrel and silver solder a hand made recoil lug into this. The result is robust enough to handle any recoil force that this mighty cartridge can generate. It also results in far less inletting of the forearm, which would have otherwise presented a problem for my intent of making that appendage round-bottomed and more trim. The action is bedded very tightly to the stock, admitting no play on recoil. Sandy also removed a nasty scratch that had somehow happened to the barrel and reblued the metal.

Fitting, Final Shaping & Finishing

My brother and I agreed that this stock should be much more trim than what one typically sees on a dangerous game rifle produced today and dramatically more trim than the factory stock. If you handle the original British sporting rifles you will be struck with their compactness and liveliness in the hands. Clublike, they are not.

Notwithstanding the massive character of the Ruger magnum action and the heavyweight barrel on this rifle, the stock could be made to be lithe and yet have a wider and deeper butt to better distribute recoil force and still afford sufficient wood around the action to maintain integrity (the Ruger inletting is more radical than for a Mauser and there is little web to support a crossbolt). To this end, my brother reshaped and slimmed the stock, preserving the pattern while reducing almost all the dimensions. This requires great skill because it entails re-cutting things like the shadowline, for example.

An enormous amount of labor time goes into stock finishing. This is an area where shortcuts will distinguish a fine stock from a decent stock. My brother labored over the finish until it was the perfect balance of satin fineness without any shiny character. Checkering was performed by Tim Smith-Lyon (Classic Checkering), whom I have come to trust for all my rifle projects.

Right profile of the completed rifle

Closeup view showing the replacement bolt handle designed and installed by Satterlee Arms, as well as the wrapover point pattern checkering on the wrist

Slimmer, round contour forearm with wrap around point pattern checkering

Inletted island swivel base, silver escutcheon and Dressel English style grip cap

Traditional pancake cheekpiece with shadowline on buttstock

Closeup view of the right side showing the replacement bolt handle, cross bolt and the trim lines of the forearm

Load Development and Shooting

Load Development

The original factory load pushed a 410 grain round nosed bullet at 2371 fps and this load, when zeroed at 150 yards, never deviates more than 1.5 inches above or below the line-of-sight out to 175 yards. It also drops less than 4 inches at 200 yards and the remaining velocity of roughly 1840 fps at that distance is probably sufficient to properly expand most softpoints in this caliber. That is as far as I would ever attempt to shoot with this rifle in extremis (not even a world class trophy opportunity would tempt me to fire such a load from the prone position, so that also limits the practical range). So, a muzzle velocity of 2375 fps with a Woodleigh 410 grain RN became my target load.

Bullets

While there are many good .416 caliber bullets on the market, accruing to the popularity of this caliber, I focused my load development on the heavier bullets for dangerous game. This rifle is quite heavy and no matter what load was made for it using a 300 to 350 grain bullet, with whatever flatness of trajectory, its not about to become an all-around rifle, simply because of the heft (at least for me). On the other hand, the ability to hunt a wide range of game with a single rifle is advantageous - if it can be made to work with the scope sighted for both loads.

With that said, I did develop a load for the 350 grain Barnes X-Bullet (original style), simply because I had them on hand. If one were to attempt a one rifle battery and include plains game this would be quite feasible, so long as shots were kept to reasonable ranges (usually not a problem in Africa). This was one of the great attractions of the legendary .450/.400 Nitro Express when it first appeared in the early 1890s, that it offered an all-around big game utility with both 300 grain and 400 grain bullets. When the .416 Rigby appeared, almost two decades later, it also was offered with a lighter bullet weight for the general run of plains game.

The preferred dangerous game bullet for the .416 Rigby is the 410 grain Woodleigh Weldcore RN, which is a near copy of the original bullet form, improved by a bonded core. It doesn't get more retro-vintage classic than that, yet with the benefit of more modern technology. These are loaded by Norma in their professional grade ammunition and also by Kynoch.

The big 450 grain Woodleigh softnose bullet is included in the load development also because Geoff McDonald, proprietor of Woodleigh, has been promoting the superheavyweight bullets in the big bores, with Kevin "Doctari" Robertson weighing in with supporting arguments in their favor. I thought I would give them a try in terminal performance testing, so I worked up a load.

Following the fire that destroyed the Woodleigh Bullets factory in November 2021, Woodleighs in most calibers, but especially in the big bores, have become essentially unavailable. We can only hope that these outstanding bullets will return someday. The latest information on the Woodleigh website is that rebuilding is well underway, but that it will be some time before the more obscure calibers return to production.

Undeniably, there are alternatives. The Barnes TSX, Nosler Partitions and the Swift A-Frames cannot be faulted for performance. Still, my preference is for a round-nosed or flat-nosed softpoint rather than a spire-point.

Once upon a time, the only bullet available in the US for a big bore dangerous game rifle was the old Hornady Interlock round nose. These were excellent bullets, as good as anything offered by Rigby or Westley Richards in the old days. They had thick steel jackets washed with copper, but would expand modestly and penetrated extremely well. Ballistically matching full metal jacket solids were also made by Hornady. For years, these bullets were only made in .458 and .375 caliber. I have read that a special run was done on occasion for .416 caliber. Only after the introduction of the .416 Remington Magnum and the re-introduction of the .416 Rigby was there any market for the .416 caliber.

Hornady has gone through a succession of designs in quest of a perfect dangerous game bullet. Although there was nothing to fault in the old design, the Interbond promised to remove any cause for complaint. Nonetheless, these were not around long before Hornady replaced them with the Dangerous Game Expanding (DGX) and Dangerous Game Solid (DGS) bullets. Following a spate of reports from the field of bullets shattering and fragmenting, the DGX was re-designed to become the DGX Bonded.

These newest DGX Bonded softpoints appear to be very good, and if the Woodleigh bullets only come back in Norma and Federal factory loads, then these would be my choice.When it came to solids, I found that the Ruger did not feed all flat-nosed bullets well. It jammed on the original pre-production experimental style of North Fork Technologies flat point solids that Mike Brady shared with me (not the design currently being manufactured), although it feeds the (now discontinued) Barnes Banded Solid FN perfectly, which has a smaller meplat and more rounded nose. I would have preferred the 410 grain Woodleigh RN solid, but my experience has taught me that flat nosed solids penetrate in a straight line, whereas round nosed bullets of most forms are extremely prone to deviation. You can see that evidenced in the penetration data on my wound ballistics site. So, here I prefer to depart from tradition and go with what works best. However, when I tested the Barnes Banded Solids in my rifle they grouped significantly off from the sighted in point of impact for the softpoints, which may mean that I'll have to use something else. There's no usefulness in a solid that hits inches away from the aimpoint and I do not intend to load and use only solids.

Selection of bullets used in load development: (L to R) 1) 350 gr Barnes X-Bullet, 2) 400 gr Barnes Banded Solid FN, 3) 400 gr Hornady

Interlock RN softpoint, 4) 410 gr Woodleigh Weldcore RN softpoint, 5) 450 gr Woodleigh Weldcore RN softpoint

Propellant

I thought that a very slow burning propellant would work best in this cavernous case and at one time contemplated using Hodgdon H-1000. Consulting all my reloading data sources, however, persuaded me to try something a bit faster, in the form of IMR-7828. This is an outstanding powder for the big Rigby. For standard loads, one need look no further. The accuracy and round-to-round consistency delivered by IMR-7828 are excellent, with the standard deviation on muzzle velocities being less than 10 fps with most loads. I have found this to be true also in the .340 Weatherby. The .416 Rigby is routinely loaded to lower pressure than its SAAMI design specification of 52,000 psi, but the maximums shown in the table below are, I believe, close to that pressure.

At first blush, IMR-7828 seemed too slow burning to be practical with the 350 grain Barnes X-Bullet. I expected a little leftover case volume, but sure enough, this powder was quickly filling the case, so I switched to Hodgdon H-4831SC with the lighter bullet weight. This too was an excellent performer.

Reduced Loads and Reduced Recoil Loads

Despite the success of my initial loading efforts using IMR-7828 and H-4831, I quickly felt the need to try something else in an endeavor to develop reduced loads that were less punishing from the bench. The new goal was to deliver the same performance as the old .450/.400 Nitro Express, which drove a 400 grain bullet at 2125 fps. This was the first nitro express, the grandfather of them all, which arrived about the same moment as the .303 Lee-Metford cartridge in the early 1890s, years before Rigby launched the venerable .450 Nitro Express. It was extremely popular and probably accounted for more big game than all of the other big bores combined. There was a twin .400 Jeffery using a more robust 3 inch case that was also immensely popular.

In 1905, Jeffery cloned its rimmed .400 to create the rimless .404 Jeffery, which became the most popular big bore in Africa in the 20th century, owing to its adoption by several East and Central African nations for their game departments, coupled with the fact that an ordinary Mauser action could accommodate the cartridge. It too, pushed a 400 grain bullet to about 2125 fps in original loadings. The muzzle velocity was subsequently increased in recent decades to about 2300 fps, but it was the original load that won its repute and was, in large part, the inspiration responsible for bringing the .416 Rigby into existence in 1911 as a cartridge for magazine rifles.

Lastly, and I offer this merely for whatever it's worth, there is the question of what the actual muzzle velocity of the original .416 Rigby loads truly were. According to Kevin "Doctari" Robertson, the old Rigby loads only generated about 2150 fps; this based on his chronograph measurements from five boxes of 1950s vintage Kynoch ammunition ("North Fork's .416 Heavyweight", Man Magnum, May 2013, pg. 27). Now, it is possible that Rigby's original proprietary loadings achieved their quoted muzzle velocities. I think this is likely given that they were touted as being verified by the Field magazine in open trials. However, it is also likely that Kynoch downloaded the ammunition over time, perhaps in response to user complaints about recoil.

Reduced loads with something as slow as IMR-7828 are not ideal and in any case the whole theory behind my investigation was founded on the suspicion that the propellant weight was a major contributor to the recoil. There is a reason why the .416 Rigby kicks a lot harder than a .458 Lott. I think both a larger propellant charge and also the bottleneck case design are contributors (although that may be counting the same effect twice in different ways). Using a relatively faster powder like H-4350 allows as much as a 10 grain reduction in the charge weight with full performance muzzle velocities and 15+ grains less for reduced velocity loads.

But maybe this wasn't going far enough. If you think about the burn rate of Cordite in the original load, as compared with modern propellants, then we ought to be using something more like IMR-3031, or perhaps faster still. Contrary to popular misconception, there were different grades of Cordite even in loading small arms ammunition. The sticks loaded in medium and big bores were thicker than those loaded in the .303 Lee-Metford and .256 Mannlicher. Still, no modern propellant recommendation for the .416 Rigby comes anywhere close to the original Cordite in burn rate. As with black powder expresses, there is a formula for recreating the original performance of older nitro expresses using modern propellants. In this case, it is using Alliant Reloder-15 in a ratio about 1.2 times the original Cordite load, according to vintage rifle expert Ross Seyfried. (Important Note: This conversion does not work for nitro-for-black Cordite loads, which used a very different bulk granulated form of propellant.) Reloder-15 is slower than Cordite (obviously), but significantly faster than H-4350, so I wanted to give that a try.

According to the 1926 Imperial Chemical Industries (Eley & Kynoch) ammunition catalog, the Cordite load for the .416 Rigby was either 70 grains for softpoint or 71 grains for solid bullet loads for a muzzle velocity of 2300 fps. This is a bit below the oft quoted standard velocity for the Rigby, but I was aiming for something reduced below even that level anyway. This muzzle velocity is also for a 26 inch barrel, so it must be reduced for the 23 inch barrel of the Ruger by 50 to 75 fps.

The Cordite load for the .450/.400 Nitro Express was 60 grains. That translates into 72 grains of Reloder-15 to approximate .450/.400 Nitro Express performance. Astoundingly, even in the larger case, it does. I assumed that an equivalent load in the .416 Rigby would be probably a few grains more to account for the slightly larger case capacity, however the 72 grain Reloder-15 load produces 2180 fps with the Hornady 400 grain bullet, which is very comparable to original .450/.400 Nitro Express performance.

I followed this load series up to the Hornady book maximum for the .404 Jeffery, which is a very similar but slightly less capacious cartridge; this load of 76 grains produces about 2278 fps. All of these reduced loads deliver appreciably less recoil than full power loads with the slowest propellants, and the Reloder-15 seemed to burn more consistently than the reduced charges of H-4350. If one believes the validity of the Cordite-equivalent Reloder-15 conversion rule, then a nominal standard load in the Rigby might be as much as 84 to 85 grains of Reloder-15. I am skeptical, as that sounds too high for this propellant, and I would caution anyone to approach such a load very carefully. I would also never attempt to attain the much higher than original velocities that some sources have shown with very slow propellants (2450 to 2600 fps with 400 to 410 grain bullets); it is not a sound assumption that one can achieve such performance enhancement equally safely with a substantially faster burning propellant, so don't try to match the performance of the Weatherby while thinking you can keep the recoil down.

These first efforts with both H-4350 and Reloder-15 yielded iffy results because, while the recoil was substantially reduced as hoped, the shot-to-shot velocity variation was too extreme to be conducive to accuracy, sometimes more than 100 fps. A solution to this is case filler to keep the powder against the primer and, in effect, reduce the case volume. It is a recommended approach for handloading nitro expresses, but these generally have either a straight taper or a very slight shoulder, not the more pronounced bottleneck of the .416 Rigby. However, I have used this technique in my Martini-Henry rifle and these are reduced loads (or no higher than original ballistics), so it should not present a pressure hazard.

Dacron polyester filler (pillow ticking) is often touted as the material of choice and it has several characteristics to commend it, including its natural slipperiness and high compaction. However, I have discovered one concerning aspect that has led me to consider other alternatives. Polyester fiber that remains in contact with nitrocellulose can chemically react with the propellant, altering the appearance of the propellant and the physical characteristics of the polyester. The propellant becomes discolored, its coating stripped off; almost certainly altering its burn rate. The polyester takes on a melted appearance.

Comparison of nitrocellulose propellant: a) original condition, b) from a cartridge where it was pressed in contact with polyester fiber

Polyester fiber altered by contact with nitrocellulose

One could fall back on the old 19th century filler standby, cotton wool, but this is much less compressible and has appreciably higher friction, so it would cause pressures to climb more steeply. The alternative that I have come to prefer is open cell foam, such as backer rod. I obtained a 200 foot roll of 5/8 inch diameter open cell polyethylene foam backer rod online, which I cut into 1 inch lengths for loading. The 5/8 inch diameter completely fills the inner case diameter and it crushes easily to hold the powder in place beneath the seated bullet. Polyethylene is also very unlikely to react with most solvents, so I think it is safer in that respect than Dacron polyester.

When using a short column of open cell polyethylene foam (I used one inch height), the loads suddenly came to life. I got excellent consistency and no worrisome pressures using both Reloder-15 and Hodgdon H-4895. The H-4895 gave slightly lower velocities in general and the sweet spot for shot-to-shot consistency, a node for the combustion harmonics, happened at one grain less than for Reloder-15. The same combustion node behavior was observed for the 350 grain and 450 grain bullet loads. All of the loads exhibited good accuracy and some were outstanding. I intend to work up a similar series with Hodgdon Varget someday, since it is more temperature stable than Reloder-15 and has almost the same interior ballistics.

Even with the foam over the powder, I honestly do not think any of these loads exceed the industry maximum average pressure specification. It stands to reason that a moderately slower propellant will produce lower chamber pressure than Cordite with loads that do not exceed the original performance. If you push past 2375 fps with a 410 grain bullet, I don't know. There is probably some margin, but I can't say where it ends. Most modern loads with slower propellants achieve the maximum average pressure limit around 2450 to 2500 fps.

Disclaimer

Warning: Use this load data at your own risk. No liability is assumed for the use of this data in any other firearm. It appeared to be safe in the test rifle, but was not subjected to pressure testing. Exercise safe reloading practices. Starting loads should always be reduced by 5 to 10% from the maximum load.

Table of Load Development Testing

| Bullet | Charge | Muzzle Velocity | Notes |

| .416-350 gr Barnes X-Bullet | Hodgdon H-4831SC | Seated to cannelure; 3.680 in OAL | |

| 102 gr | 2546 fps | SD 8 fps | |

| 103 gr | 2576 fps | Accuracy potential; SD 7 fps | |

| 104 gr | 2599 fps | SD 13 fps | |

| Alliant Reloder-15 | Reduced loads to .450/.400 Nitro Express level; Seated to cannelure; 3.700 in OAL; 5/8 x 1 in backer rod filler | ||

| 75 gr | 2317 fps | SD 19 fps | |

| 76 gr | 2345 fps | Sweet spot for this bullet weight; SD 1 fps | |

| 77 gr | 2378 fps | SD 4 fps | |

| 78 gr | No data | ||

| 79 gr | 2439 fps | SD 40 fps | |

| .416-400 gr Barnes Banded Solid FN | IMR-7828 | Seated to second relief groove; 3.705 in OAL | |

| 98 gr | 2380 fps | Accurate and consistent; SD 8 fps | |

| 99 gr | 2423 fps | Accurate and consistent; SD 8 fps | |

| 100 gr | 2460 fps | Accurate and consistent; SD 7 fps | |

| 101 gr | 2492 fps | Accurate and consistent; SD 4 fps | |

| .416-400 gr Hornady RN SP | IMR-7828 | Seated to cannelure; 3.635 in OAL | |

| 97 gr | 2337 fps | Consistent; SD 6 fps | |

| 98 gr | 2419 fps | Consistent; SD 8 fps | |

| 99 gr | 2448 fps | ||

| 100 gr | 2462 fps | Consistent; SD 8 fps | |

| 101 gr | 2534 fps | Maximum; SD 23 fps | |

| Alliant Reloder-15 | Reduced loads to .450/.400 Nitro Express level; Seated to cannelure; 3.635 in OAL; No filler | ||

| 72 gr | 2182 fps | Duplicates .450/.400 Nitro Express Cordite load; SD 37 fps | |

| 73 gr | 2180 fps | SD 17 fps | |

| 74 gr | 2209 fps | Very consistent; Sweet spot for RL-15; SD 4 fps | |

| 75 gr | 2238 fps | SD 19 fps | |

| 76 gr | 2278 fps | Hornady maximum load for .404 Jeffery; Moderate recoil; SD 33 fps | |

| .416-410 gr Woodleigh Weldcore RN SN | IMR-7828 | Seated to cannelure; 3.740 in OAL | |

| 98 gr | 2284 fps | SD 82 fps | |

| 99 gr | 2345 fps | Consistent; SD 10 fps | |

| 100 gr | 2430 fps | Accuracy potential; very consistent; SD 1 fps | |

| Hodgdon H-4350 | Reduced loads to .450/.400 Nitro Express level; No filler; Seated to cannelure; 3.740 in OAL | ||

| 76 gr | 2085 fps | SD 29 fps | |

| 77 gr | 2070 fps | Wide velocity variation; SD 60 fps | |

| 78 gr | 2121 fps | SD 21 fps | |

| 79 gr | 2107 fps | Wide velocity variation; SD 74 fps | |

| 86 gr | 2247 fps | Full power load series; sharper recoil; SD 18 fps | |

| 87 gr | 2271 fps | SD 22 fps | |

| 88 gr | 2273 fps | SD 23 fps | |

| 89 gr | 2364 fps | Near standard load; not maximum; Wide velocity variation; SD 51 fps | |

| Alliant Reloder-15 | Seated to cannelure; 3.740 in OAL; 5/8 x 1 in backer rod filler | ||

| 72 gr | 2170 fps | Reduced loads to .450/.400 Nitro Express level; SD 9 fps | |

| 73 gr | 2181 fps | SD 11 fps | |

| 74 gr | 2198 fps | Duplicates .404 Jeffery; Sweet spot for RL-15; SD 2 fps | |

| 75 gr | 2231 fps | SD 8 fps | |

| 76 gr | 2257 fps | SD 17 fps | |

| Hodgdon H-4895 | Seated to cannelure; 3.740 in OAL; 5/8 x 1 in backer rod filler | ||

| 72 gr | 2107 fps | ||

| 73 gr | 2130 fps | Duplicates .404 Jeffery; Sweet spot for H-4895; SD 1 fps | |

| 74 gr | 2137 fps | SD 7 fps | |

| 75 gr | 2227 fps | SD 28 fps | |

| 76 gr | 2255 fps | SD 57 fps | |

| .416-450 gr Woodleigh Weldcore RN SN | IMR-7828 | Seated to cannelure; 3.740 in OAL | |

| 93 gr | 2161 fps | SD 20 fps | |

| 94 gr | 2185 fps | Accuracy potential; very consistent; SD 6 fps | |

| 95 gr | 2256 fps | Maximum; consistent; SD 21 fps | |

| Alliant Reloder-15 | Seated to cannelure; 3.725 in OAL; 5/8 x 1 in backer rod filler | ||

| 71 gr | 1978 fps | Reduced loads to .450/.400 Nitro Express level; SD 6 fps | |

| 72 gr | 1996 fps | SD 6 fps | |

| 73 gr | 2017 fps | SD 4 fps | |

| 74 gr | 2042 fps | Sweet spot for RL-15; SD 1 fps | |

| 75 gr | 2085 fps | SD 2 fps | |

| 76 gr | 2159 fps | SD 10 fps | |

| 77 gr | 2148 fps | Second sweet spot; SD 6 fps; Duplicates Norma factory load | |

| 78 gr | 2163 fps | SD 15 fps | |

Recoil

Recoil with this behemoth cartridge, when loaded to its original performance specifications with today's slow burning propellants, is prodigious; but thanks to the improved stock with its wider, deeper butt and Pachmayr Deccelerator pad, it is tolerable even from the bench. In my second shooting session I fired a dozen rounds off the bench and felt perfectly fine. Getting acclimated to the recoil of heavy rifles requires shooting with reasonable frequency, but never to excess. If you shoot 10 or 20 rounds on most trips to the range then it won't seem outrageous, and if you never do some macho endurance shooting marathon you'll never become recoil sensitive. For practical field shooting, recoil is not a problem at all (other than prone shooting, which is assuredly a very, very bad idea).

On the other hand, when loaded with faster burning propellants to the 2125 to 2175 fps level of the preponderance of dangerous game nitro expresses, including the original .450/.400 Nitro Express, the .400 Jeffery and the .404 Jeffery, this cartridge can be made to perform very nicely and the recoil is rather mild in a 10-1/2 or 11 lb rifle. I would not hesitate to take a prone shot with these reduced loads. In real world performance, using advances in bullet metallurgy, it is a superior hunting arm to anything taken afield in the heyday of African safari.

Accuracy

Notwithstanding the heavy recoil, accuracy with this rifle is very, very good. I have had several groups at 100 yards with cloverleafs and bullets touching. This in spite of the fact that, although I never do this with other rifles and tried to shoot with a very erect posture from the bench with the full power loads, I got smacked in the forehead by the scope ocular ring, the second time hard enough to raise a knot between my eyes (I am fortunate that it had a rubber bumper on the rim or I would have been cut to the bone). Anyway, all of the loads were acceptably accurate, with some being scary accurate.

Classic Rifles, Pistols and Cartridges Main Page

Copyright 2011 - 2023 -- All Rights Reserved